to hold

to miss

to remember

In June 2017 Lynn Marie Kirby in collaboration with Sarah Bird invited the public to join them in performing a site-specific intervention, to hold to miss to remember, outside the Church during the Venice Biennale. For three days the two set out to make 100 attempts to recover the tender gesture from the stolen painting, a tenderness missing in our world today.

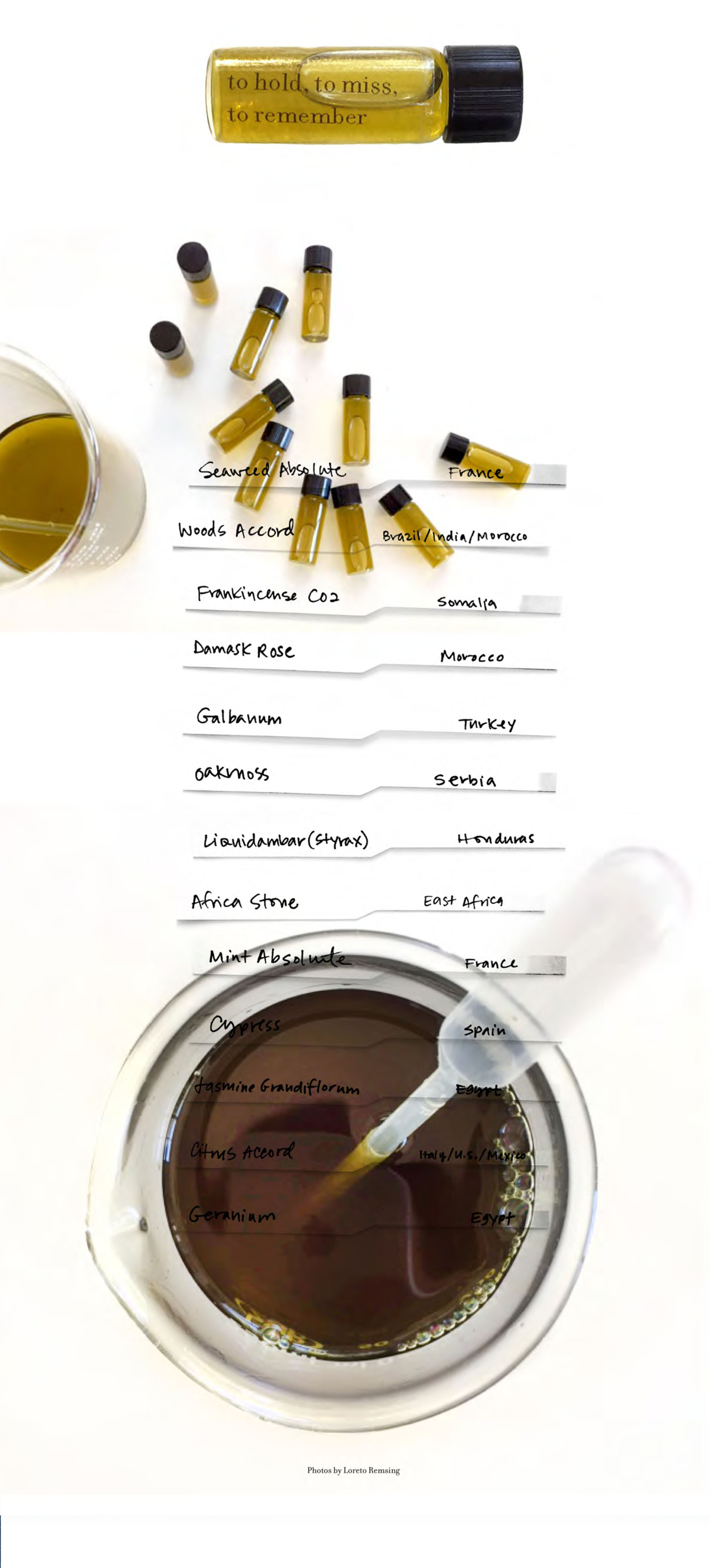

Kirby, wearing a scent created for the project, dressed as the missing Madonna. Sitting in one of two chairs, she wrapped her arm around participants when they sat in the empty chair next to her. Bird marked in chalk on the herringbone brickwork of the campo the number of attempts enacted. Afterwards each participant was given a small vial of the scent as a touchstone of remembrance.

Cloak by Tiersa Nureyev • Design by Eing Opastpongkarn

Why this interest in tenderness and Bellini?

LYNN: Tenderness can be found in many of Bellini’s paintings. Bellini’s work is scattered throughout Venice. When my son was about ten months old, and I had left the Bay Area to live again in Paris, where I had spent time as a child, I read Julia Kristeva’s essay on Bellini’s representations of motherhood. Kristeva writes about the way Bellini depicts the mother and child occupying their own spaces, independently looking out of the picture frame, not locked in one another’s gaze as so much of Western painting depicts the mother/child bond. This inspired me.

In terms of our project, the kind of togetherness and connection that can happen between people—that is especially needed at this political juncture—was for me represented in the gesture in the missing painting. I was especially struck, for example, by an increasing lack of compassion for the plight of refugees victimized by strict immigration policies, in Europe, and in the United States following the U.S. presidential election of 2016.

SARAH: My love of the paintings of Giovanni Bellini was sparked by my exposure to him while I was in college—his delicate and luminous layers of color, the tenderness of the depictions of humans and nature in both form and content. The tenderness between people so beautifully depicted by Bellini connects us to the current refugee and immigrant crises. Tenderness can disarm otherness. I believe art has the ability to convey complex meaning and spark thoughtful responses. Our site intervention in Venice was an attempt to connect history and the present.

How did you frame the re-enactment?

LYNN: The performance itself is framed by the Venice Biennale at a time when residents and visitors are primed for public events. Our

site intervention took place outside of the church within the larger frame of the Biennale. Within that framework we manufactured our own place. I was struck by how intrigued people were by what was essentially an abstract concept, albeit acted out in concrete ways. Our goal was to locate

missing tenderness in a shared experience of simple touch and smell.

We went to mass on Sunday morning to meet the priest. After mass we talked to him about our project, showed him our flyer, and discussed sitting outside of the church.

The priest said that the painting was not only missing from the church but also from our lives. The tenderness represented in the painting had been

withdrawn from all of us when the painting was stolen.

Immediately he was with us!

He suggested we find chairs or a bench from inside the church instead of bringing something from afar. He showed us the chairs and benches we

might choose from. We were also given a place to change in the vestibule.

SARAH: Together, we walked the site and practiced careful observation. How does the sun move across the sky? How do we situate ourselves in relation to the walkways and the bridge that lead us into the campo? How do we occupy it?

I need to map in my head the places I inhabit. I like to know where I am spatially, a form of geolocation. Which way will the sun move across this site? Which way is the expanse of the lagoon? Are the bells I hear from that tower, or are they coming from elsewhere and bouncing off the walls and the water? Within the narrow vistas of Venice’s alleys, a campo like this one is a respite.

LYNN: We took lots of pictures to note the light and chart how it would change over the course of the day. It is difficult to sit in the bright sun, and so we wanted to make sure to choose a spot in shade. Our shared background in filmmaking made it fun to study our site as a location. We had looked at images on Google maps, and Luca Muscara, the Venetian friend I was staying with, had graciously sent us many pictures beforehand, but feeling the space in person was totally different.

SARAH: The pattern of the bricks and the stone of the campo leant itself to subtly delineated areas. We looked at the way people walked through the space when they had a destination and the way people meandered when they didn’t.

Lynn would be clothed in a deep blue cloak, another way of framing. We felt we needed a way to mark our intention; clothing became part of that—deep blue in homage to the color prized for its rarity and expense in Bellini’s time.

We had originally been thinking about a small bench.

LYNN: We had looked at benches online at Ikea Mestre and plotted lugging a bench on the Vaporetto! We were glad to receive chairs from the priest. My friend Ann Hatch was telling me about a wood workshop run by her husband. In the morning the participants are asked to make a chair; only after they have finished the chair can they sit and have lunch together.

SARAH: We were greeted with such generosity by the priest and were able to borrow two matching ecclesiastical-looking chairs. Their dark wood patina and crown-like backs further framed our simple placement in the campo.

Lynn sat in one chair and waited. The other chair, directly touching hers, served as both an invitation and an indication of absence. A chair, formed to fit the human body—in contrast to, say, a table, on which objects, not humans, usually rest—is particularly ripe with absence when no human occupies it.

And then there was Lynn’s stillness. With her back to the church, she sat on the left, her presence open and generous, offering a silent invitation. The work of translating that silence into language, and action, was mine.

LYNN: Sarah functioned as the barker, introducing the public to the project and framing it in relation to the missing painting. Because she speaks multiple languages, she was able to talk to almost anyone, and if not, she would point to the flyer on which the project had been translated into twelve languages. I sat in silence and stillness, present.

SARAH: A good many passersby said “no” out of confusion or habit, but I was also surprised by the openness and curiosity of those who said “yes.” They told me, of course they knew the painting! Some approached Lynn (the Madonna) with a self-conscious giggle, and many more approached her with respect. Once a participant was seated, I stepped back, removing myself.

I was moved by our participants’ willingness and ability to enter the quiet space of non-action that we had created. Lynn held them with her body. Her quiet presence held them too and gave them permission simply to be. I was surprised at how many of the participants seemed to drop quickly into a meditative state when they allowed themselves to sit and be held—to have an authentic moment with another human being. I was also aware of being a white Anglo woman asking strangers to trust us with their bodies and their feelings. I wondered how my interactions with others would have been affected had I appeared more “other” to any one of them in the Venetian Campo.

LYNN: The geographer Yi-Fu Tuan talks about the vertical space of the cosmos, how we used to look to the heavens to think outside of ourselves, the self not at the center of the universe.

In today’s more linear view of life, we have lost much of our connection to the sacred, yet specific sites still connect us to the transcendent. The campo makes this connection: the sound of the church bells from the tower above gave form to the silence of sitting, and the brick beneath our feet anchored us to the earth.

The square outside of the church feels as sacred as the inside of the church with all its glorious artworks. The dimensions of the square, with squares set inside other squares in a repeated framing pattern—like the infinitely repeating patterns of Islamic architecture—has a divine structure.

SARAH: The campo establishes a visual rhythm with its brick pattern of herringbone sections set within stone-outlined squares. The two materials offset one another. The stone creates lines of latitude and longitude. The brick pattern marks the campo as a special and considered space.

The terracotta bricks are worn, their color softer and warmer than the more usual grey stone. The color emits a glow unique to this campo.

Counting the bricks within each stone square, we discovered that each square within the stone lines contains 300 bricks, so our goal of 100 attempts could best be marked by marking one brick in every three.

Lucia, one of the women who works in the cloister next door to the church, told me that Campo Madonna de l’Orto is one of the few remaining brick squares in Venice, most having been paved over with stone, and raised up over the decades against the sinking land and rising waters.

Each time a participant joined Lynn on the chairs, I walked to our herringbone square, counted three bricks and made a mark. The repeated ritual of making a chalk mark on the brick served to acknowledge our attempts to restore what is missing, and by doing so, to frame the breadth of our intention.

Over the three days 55 people participated. We have 45 more attempts remaining!

LYNN: Outside we heard the sounds of the birds, tolling bells, water sloshing in the canal as boats go by, echoes of people passing, but also the

majestic sounds of labor, the banging and sawing of construction at the

edge of the campo, as two workmen built a large yellow wooden structure to house their materials. This rhythm surrounded our attempts to

find the missing gesture.

The men constructing the yellow structure were ultimately going to rebuild the bridge over the canal that leads to the campo and church. Both men in the work crew came over to participate.

SARAH: We had made a point of introducing ourselves to the workers in the campo, and I chatted with them each day for a few minutes. Although always polite, they were initially skeptical of our project and joked about it between themselves. Over a few days and our steady reappearance their confusion and laughter gave way to curiosity. On the second day of our attempts, one of the workers sat with Lynn for over twenty minutes and came back again the next day.

LYNN: It was the longest any of us had sat together. An electricity and a feeling of simplicity passed between me and the worker. As I held him, we sat and listened together to the sounds surrounding us. This meeting of two people was the most surprising aspect of the project. In all the planning and preparation, I had never thought about what it would feel like to be sitting with my arm around a stranger, holding this person sitting next to me. I knew we wanted to find the missing tenderness, but I was unprepared for the raw power of the gesture.

One woman wept, and although mostly we sat together in silence, a few people spoke to me.

One woman told me that she held her children when they were growing up, but that she had never been held, and now that her children were grown, she was glad that she too could finally be held.

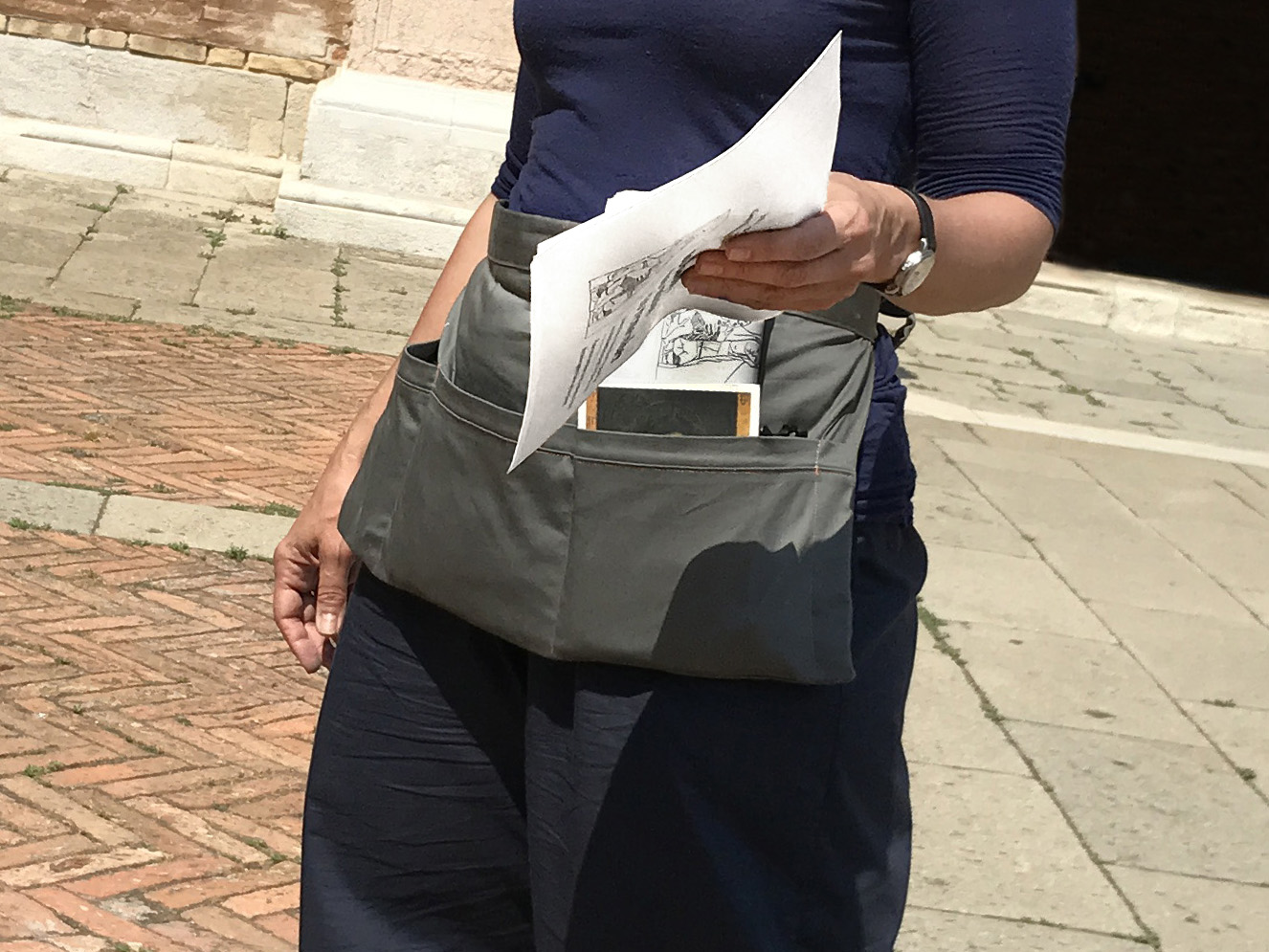

SARAH: I have our pretty flyer in my hand, something to point to and describe, and it helps not to be empty-handed when approaching strangers. “Would you like to participate in our art project, a reenactment of the stolen Bellini painting?” “There is a stolen painting?” they ask. “Yes, and it’s still missing. Would you like to sit with my colleague and evoke its spirit, the tender gesture we are now missing?”

Some people are closed. Just as many are open and generous with their time, their questions, and their enthusiasm for our project.

Lynn and I decide that I will not say ahead of time that they will be given a vial of scent after participating. It confuses the request up front and adds a transactional quality we don’t want. But every single person who participates is touched by our exchange at the end. When Lynn gives them the scent, they bow; they say thank you. Quite a few participants come back to me and want to know about the scent, and I show them our list of ingredients, and their origins in the flyer.

And it becomes clear to me we are engaged with the public in an exchange of generosity.